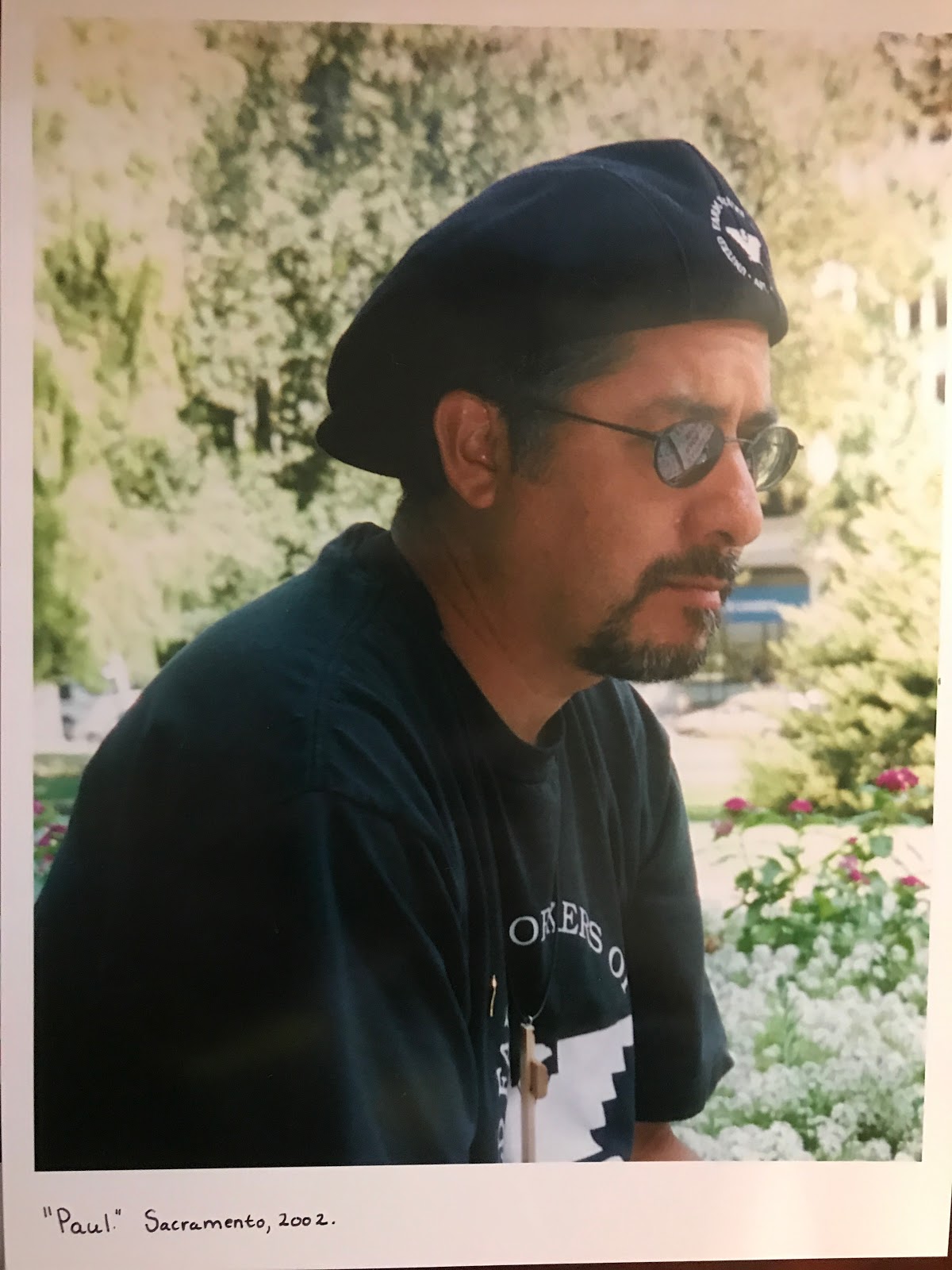

CHLX Professor Dr. Paul Lopez

For the last five years, Dr. Paul López and his colleagues in the MCGS (Multicultural & Gender Studies) department at Chico State advocated for a Chicanx/Latinx major. It was imperative to him that Chicanx/Latinx studies be extended as a Bachelor’s degree, and not only offered as a minor.

“It could be argued that this should have happened 15 years ago,” López said, noting that the major could have been used long before it was actually implemented. “Latinos are the fastest-growing population and the largest in California by far.”

These growing Chicanx/Latinx populations mean that the demand for knowledge of their culture and heritage is increasing. It is necessary to educate people who are planning to work with Chicanx/Latinx communities so that they are able to be strong, compassionate, and informed allies. Without the push from López, CSU Chico may have never had the opportunity to offer this major.

Kassandra Garcia, a senior CHLX major, reflected on the impact Dr. López has on the program.

“Dr. López is one of the few faculty members of the CHLX department. Starting as a freshman, he was one of my first MCGS and CHLX professors. He inspires the students to learn about the oppressions of the CHLX community,” Garcia said. “He inspired me to further my education with CHLX studies.”

With 40% of California’s population being Chicanx/Latinx, graduates of this degree have endless possibilities for where they could take their career post-college. Whether it be a career in the nonprofit sector, consumer data, or public school system— the call for cross-cultural skills to serve our complex multicultural society is persistent. The desire for this community to feel seen, heard, and equitably served is one of the many reasons why López was so adamant about implementing the new Bachelor’sdegree for our students.

Why declare a major in Chicanx/Latinx Studies? “It is mainly about your ability to market yourself,” López said. “Demographically, there is an advantage now. California and states in the Southwest are going to need specialists, people who know this community.”

It was the same thought López had when he started his college career. Originally considering a degree in African-American studies, he decided to focus his attention on Chicanx/Latinx studies, as he thought there would be greater opportunities. Fully dedicating himself to the courses he was taking, López knew by the time he was a junior at California State University, Northridge that he wanted to be a professor and teach the material he was so passionate about.

“I spent my last two and a half years pouring over books. I had no social life,” López recalls. The studying prepared him for his next step: writing a letter to a professor at the University of Notre Dame who was known for his expertise on Mexican Immigration at the time. “He actually wrote me back and asked me to apply.”

In the Spring of 1982, Lopez was accepted into the sociology program at Notre Dame. Since there were no Ph.D. Chicanx/Latinx programs, and few programs in which Chicanx/Latinx communities received adequate attention, he made the decision to move his life across the country. From Northridge to South Bend, Indiana, López earned his Master’s degree in Sociology— specializing in Mexican Immigration.

Planning on receiving his doctorate degree, his life took a shift when his wife became pregnant with their first child. Feeling like going back to California was the right choice for his blooming family, López took a break from school and started teaching part-time. It was only 4 years later that he realized he wanted to obtain his doctorate degree in sociology. Still focusing on Mexican Immigration, he went deeper into the analysis of the labor market.

Idaho was where he was officially hired as a Mexican-American Studies professor. Since López never had the opportunity to focus his academic career solely on the Latinx community, this was a big step for him, one that validated all the work he had put into researching the Chicanx/Latinx community. Although he was happy with his teaching accomplishments in Idaho, he knew he did not want to stay there forever.

That is why, when he received two offers, one at Chico State and one at Fresno State, he knew it was his chance to return to California. With a wife, three kids, and three dogs, it was important to López that he makes the decision based on where his family would thrive best.

It turned out that Chico was the best option for them. He accepted the offer and was hired alongside Dr. Susan M. Green, another MCGS professor at Chico State who pursued a career in Chicanx studies. Green’s current research concentrates on the history of Chicanx movements and their fight for equity and justice. “She has been a great partner,” López said of Green.

Green feels the same fondness for López. Working together as advisors for M.E.Ch.A, (Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán) a student-run organization that functions to recruit students into higher education while advancing the civil and human rights of Chicanx students on campus, the two grew close in fighting for the new major. The two have also marched together with M.E.Ch.A on miles-long protests, where they practiced their activism and passion for equity.

“We have been the best of friends and colleagues in the struggle,” Green said, reflecting on their 22-year-long relationship. “He is willing to do anything to help students grow and be successful as people, and at any time of day.”

Part of the struggle Green is referring to was the slow response from the Chico State administration in making the Chicanx/Latinx major transpire. Despite the constant support from students, and the letters that were sent to the administration from M.E.Ch.A, it took a long time for the administration to understand how necessary this pursuit was. Even so, López insisted that it was a struggle worth advocating for.

The individuals who work closest with López commend him for his willingness to stand up for what is right and protect his students’ best interests. Instead of playing it safe and trying to win over the administration by sticking with what they knew, he pushed better resources for his colleagues and students.

“He's fought tirelessly, not only for more Chicanx/Latinx students on campus but also more faculty and staff across campus to support those students,” Green said of his impact on the lives around him. “He was part of the movement to make Chico State a Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI), which will be an enduring benefit for generations to come.”

“I had to put my foot down. Do some boycotting here and there when it was not popular,” López said. In order for change to be made, it is necessary to not accept things that so obviously need reform. This influenced the relationship López had with Chico State’s administration. “They have never been too fond of me. If I see something that is messed up and needs to be fixed, I will push the envelope.”

Such is López’s research on braceros, or guest workers from Mexico from the mid 20th century. His research examines how some former participants in the U.S-Mexico Bracero Program set down roots in the United States rather than going home when their invitation was rescinded.

“Their histories are eerily reminiscent of the current oppressive situation with undocumented immigration,” says MCGS and CHLX colleague Sara E. Cooper. “We want their brazos (arms) to do our most back-breaking labor, where they risk dangers from heat exhaustion to pesticide poisoning to Covid, and yet we don’t want to provide them health care or the dignity of a secure life with their families.”

López has published two books on the matter, The Braceros: Guest Workers, Settlers, and Family Legacies and Que Fronteras?: Mexican Braceros and a Re-examination of the Legacy of Migration.

López’s willingness to “push the envelope” encapsulates the approach taken by students and faculty of the MCGS department entirely. Their mission is to critically examine the injustices that plague our world and work to advance social justice through informed activism. The only way that this mission could be accomplished is by expanding the resources available to students and providing the best possible education as social justice warriors. It is only fitting that they extend this offer of a Bachelor’s degree in Chicanx/Latinx studies.

“This is the perfect late storm,” López exclaimed.