Carbon Farming

Farming Proactively with the Carbon Cycle in Mind

Image credit: Office of Biological and Environmental Research of the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. science.energy.gov/ber/

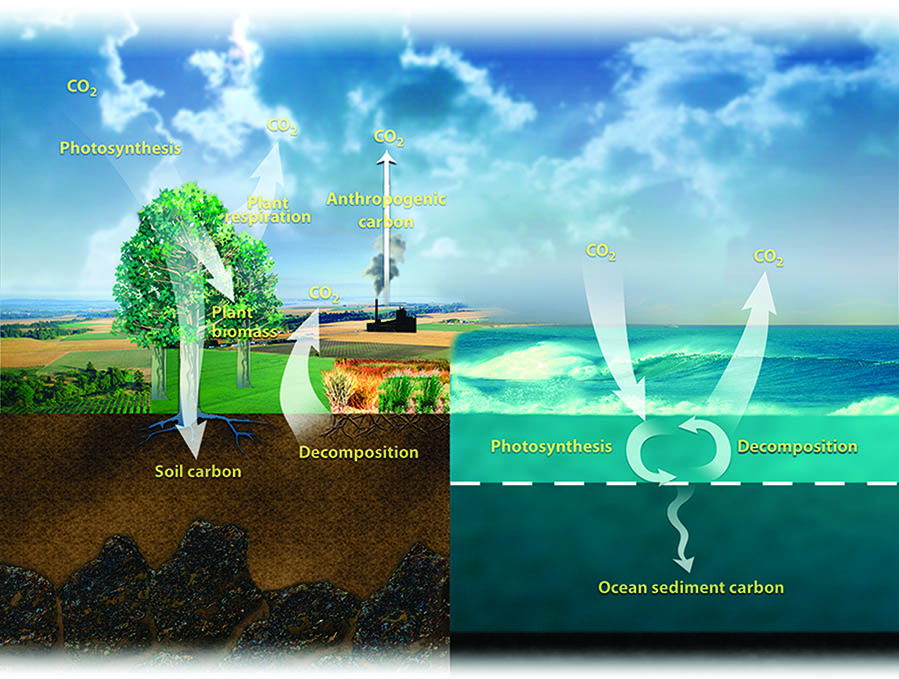

Global warming, the key driver of climate change, is the result of heat-trapping greenhouse gases (GHGs) that are building up in the atmosphere. Typically, natural earth processes cycle those gasses back and forth between land, ocean and atmosphere. However, human-caused emissions have increased so dramatically through the burning of fossil fuels and modern agricultural practices that the natural cycles cannot keep up. As a result, GHG gasses have built up in the atmosphere—where it is warming the planet—and in the ocean—where it is acidifying that environment and harming marine life.

One of the most significant GHGs is carbon dioxide (CO2), which not only heats up the atmosphere itself but considerably increases the amount of water vapor in the atmosphere. Water vapor (humidity) is itself a GHG and amplifies the warming effect of carbon dioxide. Luckily for us, there are ways to effectively work with nature's cycles—in particular, the carbon cycle—to solve this problem. The carbon cycle is a series of processes where carbon is converted into a form that can be used by plants and other living things through photosynthesis. CO2 is then released back into the atmosphere through respiration or the decay of dead organisms. That's where the concepts of carbon farming and regenerative agriculture come in. Carbon farming is a whole systems approach that works with nature to safely draw down CO2 from the atmosphere and help it accrue underground without excessive release back into the atmosphere. It is also called "regenerative" because, when done effectively, the same practices restore the natural biological functioning of the soil, improve soil health, and restore biodiversity and multiple interlocking environmental functions we depend on for food and water security and farm resiliency.

Practices that accrue carbon and best keep it sequestered underground include:

- Avoiding tillage

- Keeping the ground covered with mulches or living plants with roots left in the ground all year.

- Keeping soil microbe communities intact with additional practices such as minimizing or eliminating pesticides, herbicides and nitrogen fertilizers.

- Adaptive grazing that includes holistic management practices focused on soil health.

Additional practices such as silvopasture, cover cropping, alley cropping, and the use of windbreaks and riparian plantings draw down more CO2 via photosynthesis. When combined with practices that keep most of that CO2 sequestered, a very effective carbon farming plan can be created.

Benefits to the Planet

While there are other ways to draw down and sequester carbon and equally important actions that need to be taken, agricultural lands offer such a vast opportunity for positive impact that the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and the California Department of Food and Agriculture(opens in new window) have specifically created new funding programs for conservation and carbon farm plan development. The Carbon Cycle Institute estimates that in California alone, agricultural lands could sequester over 60 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent annually by 2030. That would more than offset the agricultural sector’s own GHG emissions. To put this into greater perspective, planting trees is often suggested as a way to sequester carbon. However, according to the Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator(opens in new window) provided by the United States Environmental Protection Agency, to sequester an equivalent amount of CO2, 992,105,159 tree seedlings would need to be planted and successfully grown for ten years!

Benefits to the Farmer

Combating climate change is not the only benefit of carbon farming. In fact, from a farmer's point of view, it may not be the most important benefit. Simply put, these practices can solve multiple problems farmers face simultaneously:

- It can dramatically decrease soil erosion and degradation.

- It can assist with water infiltration and retention (especially important in times of drought).

- It reduces the need for pesticides, herbicides and synthetic fertilizers over time, thereby reducing or eliminating the costs of those inputs.

- It reduces the amount of air pollution created by tillage.

- It reduces the amount of fossil fuels used and the associated costs by reducing tractor passes.

Although making changes to one's farming operation can take time, money, and learning to effectively implement, the benefits can more than pay off in the long run. Most farmers and ranchers report increased profits without reduction in yields once the initial transition stage is complete. That transition can happen in stages to reduce risk. For example, many farmers convert only one small section of their property at a time to gauge the impact of their choices and learn what works best in their local environment. Plus there are government, state, and non-profit programs that can help pay for the costs of transition. There may even be carbon market opportunities to provide additional income (although, at the present time, these should be seen as more likely supplemental to other programs available and benefits received).