White Oak Pastures

“For us, regenerative agriculture means that we leave the land and the system better off every year that we operate.”

The Harris family has raised cattle on the same Bluffton, Southern Georgia farm for five generations, starting not long after the Civil War in 1866. It was run in traditional ways back then and grew from a farm that mostly just sustained the people who worked on it to one that supplied several local businesses as well. After World War II, however, that traditional way of life eroded as modern methods of raising livestock and distributing meat were adopted. The family used the new chemical tools science introduced to the farming industry and the slaughtering process became more centralized and distant from their pastures. By the latter half of the 20th century, the farm only produced calves for the industrial beef production system that supplies most of the food we currently eat in this country.

On the one hand, these changes made food much cheaper and abundant, “wastefully abundant” as White Oak Pastures(opens in new window) puts it. But they say it also caused situations where the animals were no longer being raised and slaughtered as humanely as was done in the past. And it has had horrific effects on the environment in terms of topsoil loss, pesticide contamination, escalated greenhouse gasses, antibiotic resistant pathogens, etc. It also led to impoverishment of the local rural community system of farming as the necessary infrastructures to maintain local foodsheds were destroyed and food production became centralized. This was particularly true in Bluffton where the economy practically collapsed.

In 1995, increasingly disturbed by what his operation had turned into, Will Harris III(opens in new window) decided to return to a system that he thought would be much better for the environment, the animals and the people who work with them, and for the people who eat these meats. He went back to raising multiple species of animals and using the rotational grazing practices his ancestors used. Why? Harris says “nature abhors a monoculture” and calls his approach “radically traditional.”

Today White Oak Pastures produces grassfed beef, goats and lamb and pastured pork, turkey, chicken, duck, goose, guinea, and rabbit on 3200 acres. They also grow 60 different varieties of organic vegetables. They gave up feeding their animals grain, hormone implants and antibiotics. By 2000 they gave up chemical fertilizers and pesticides. And in 2016 they committed themselves to regenerative agriculture and holistic management techniques, becoming one of only 23 global Savory Hubs(opens in new window) at that time. Savory Hubs are certified to operate as demonstration sites to teach others.

Regenerative Methods

Holistic Management

Harris has come to see his operation as a living system. “Holistic management changed the way I looked at land. When I was fifty years old, I looked at the land as just kind of the medium that held the seed out so it could catch the rain and the sun. I don’t look at it like that anymore. Now I look at it as a system/cycle.”

“There is a lot of symbiosis in nature. What we do here is an imitation of nature. We call it biomimicry. It’s an effort to maximize symbiosis and there are many examples of how we try to do that.”

The animals and plants live in a symbiotic relationship along with the microbes in the soil. “The microbes feed plants which feed the animals which spread urine and feces to microbes which feeds the plants which feed the animals.” They rotate complimentary animal species side by side through their pastures using the Serengeti Rotational Grazing Model(opens in new window), a model of raising animals that actually helps regenerate the land.

“The cows graze the grass, the sheep and goats prefer the weeds, and the poultry species peck at the roots, bugs and grubs. All species naturally fertilize the land. This way, the pastures are grazed and fertilized in three different ways.” By moving the animals from place to place they avoid overgrazing. The idea is to always allow several inches of grass left to help it recover and re-establish itself. They aim to let the animals "trample 1/3, eat 1/3 and leave 1/3."

No-till, Compost, and Cover Crops

White Oak Pastures has been actively converting all of its garden sites to an organic no-till system over a number of years. The intent is to mimic nature and get the soil to eventually resemble the rich loam of healthy forests. They create their own compost on the farm using cleaned local peanut hulls, vegetable matter left from previous harvests in their garden, and the animal remains they can’t use in tallow, leather or pet chew production. They inoculate the ground remains with Lactobacillus, a bacteria that breaks down the organic material with a low pH that kills harmful pathogens. It’s an anaerobic approach, which means they don’t have to continually turn the piles, saving time, equipment, and diesel fuel. After twelve weeks, they turn the pile over once and let it sit for at least six months to be certain that all harmful bacteria and pathogens have died off before spreading it on their pastures.

White Oak Pastures also plants perennial fruiting shrubs and trees near the garden to help grow and maintain microbial networks in the soil. They plant herbs and specific vegetables near certain crops as companion crops. The idea is for the herbs to hopefully help deter insects. Some crops are chosen because they have deeper roots that can help bring nutrients up from lower levels of the soil, and legumes are used to help make nitrogen available to surrounding plants. To help suppress weeds, they use cover crops such as crimson clover, winter wheat, sudan grass, and white Dutch clover. When it is time to harvest, they try to cut the vegetables off at the base, leaving the roots in the ground to avoid disturbing the soil biology as much as possible.

The Challenges

There has been a steep learning curve. For example, Harris says, “Planned grazing is highly situational. It varies, depending on whether you are grazing annuals or perennials. It varies if it’s warm season or cool season. It varies if it’s raining or dry weather. So it requires a lot of experience, and you gotta understand that it is never gonna be perfect.”

It was also, at first, economically painful. There were many times when Will Harris wondered if he had made a mistake in embarking on this path. Harris says “we recorded financial losses for three years, and I had previously never had a year in my life in which I lost money." They had to invest considerably in infrastructure changes: fencing for smaller grazing paddocks, water infrastructure for drinking, also more livestock species. The biggest investment was in creating a plant for slaughtering and processing on his property instead of continuing to ship the animals elsewhere.

Harris felt like he had taken an incredible risk. But today he says, “it is now working financially, and I am glad that I made the changes.”

The Benefits

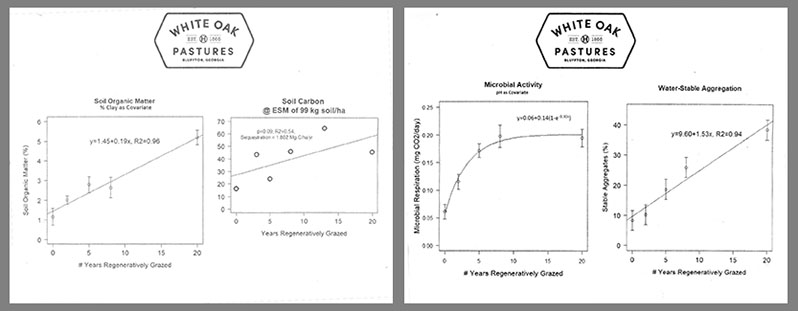

The hard work is paying off. A Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) study done by a Quantis, a third party sustainability science firm, found that White Oak Pastures offsets more than 100% of their cattle greenhouse gas emissions and 85% of the farm’s total carbon emissions. That means they are storing more carbon in the soil than their cows emit in their lifetime (carbon negative) and are, step by step, getting close to a carbon neutral operation overall. Quantis analysis included enteric emissions (belches and gas) from cattle, manure emissions, farm activities, slaughter and transport, and carbon sequestration through soil and plant matter. Because White Oak Pastures has been acquiring and converting land to holistic practices over quite a long time, they were also able to do soil sampling and model data from a number of different ecosystems in different stages of the regenerative journey. Some of the most exciting news is that in 2017 White Oak Pastures sequestered 919 tons of CO2 in the soil and their grassfed beef had a carbon footprint 111% lower than conventional beef.

White Oak Pastures also participates in the EOV (Ecological Outcome Verification) program(opens in new window) through the Savory Institute that helps farms in the process of transitioning to regenerative practices monitor their results. They take monthly samples from the same specific spots scattered throughout their property that measure soil health, and key factors related to biodiversity and ecosystem function.

Because of these impressive results, Will Harris has most recently entered into a partnership with Silicon Ranch Corporation to bring regenerative land management to almost 2,400 solar farm acres in Southwest Georgia. His sheep now provide grazing services to keep vegetation from shading the solar arrays while regenerating the property and helping to sequester carbon. The project started in 2020 has been so successful that White Oak Pastures now sponsors comprehensive multiple-day workshops on Solar Grazing(opens in new window) to help other ranchers learn how to develop similar grazing partnerships with green energy producers across the country.

Advice to Others

Will Harris advises others that plan to follow in his footsteps that they should “be prepared to experience operational losses for some period of time. The learning curve is steep and cash flow is always a challenge when you are in a capital intensive business that has thin margins.”

Still, he says, “I wish that the opportunity to make these changes had come along earlier in my career. But, I would have gone broke if I had made the changes before the market was ready.”

More from Will Harris from the video below: When I was an industrial farmer, I'd have said that I wish that you knew how hard it is, how stressful it is, how complicated it is, how much work there is . . . Now that I farm differently, that is not what I would wish for you to know.

“I wish that you could know how much fun it is, how great it is to work with friends and family, how good it is to be in touch with the changing of the seasons, how rewarding it is to see the condition of the soil improve, how peaceful it is to watch animals express their instinctive behavior, how pleasing it is to watch our community start prospering again . . .”

He’s glad he took the plunge and now teaches other people through tours, workshops and events on his farm(opens in new window).

One Hundred Thousand Beating Hearts: