Regenerating the Earth while Regenerating the Lives of People of Color

by Sheryl Karas M.A., CRARS staff

The history of black and brown people in farming in this country isn’t a pretty one. Slavery, low-paid migrant workers, sharecropping (often called slavery by another name), and a history of extreme discrimination in regards to land ownership have made it difficult for people of color to embrace a career in farming. In 1910, black people made up 14% of American farmers. But today, black farmers make up less than 2% of all farmers in the U.S.(opens in new window) even though they comprise between 12-14% of the population. To make matters worse, some of the same racial discrimination that forced them off the land have led to black and brown people being much more likely to live in food deserts (PDF) with challenging access to healthy fresh produce and meat. They are far more likely to suffer from poor health and nutrition as a result.

But today this is starting to change. Not only are some black and brown community leaders advocating for the creation of community gardens in the U.S. inner cities and more black-ownership of farms on the periphery of urban areas, people of color in many places around the world are in the forefront of embracing regenerative agriculture to help their communities survive in the face of soil depletion and climate change.

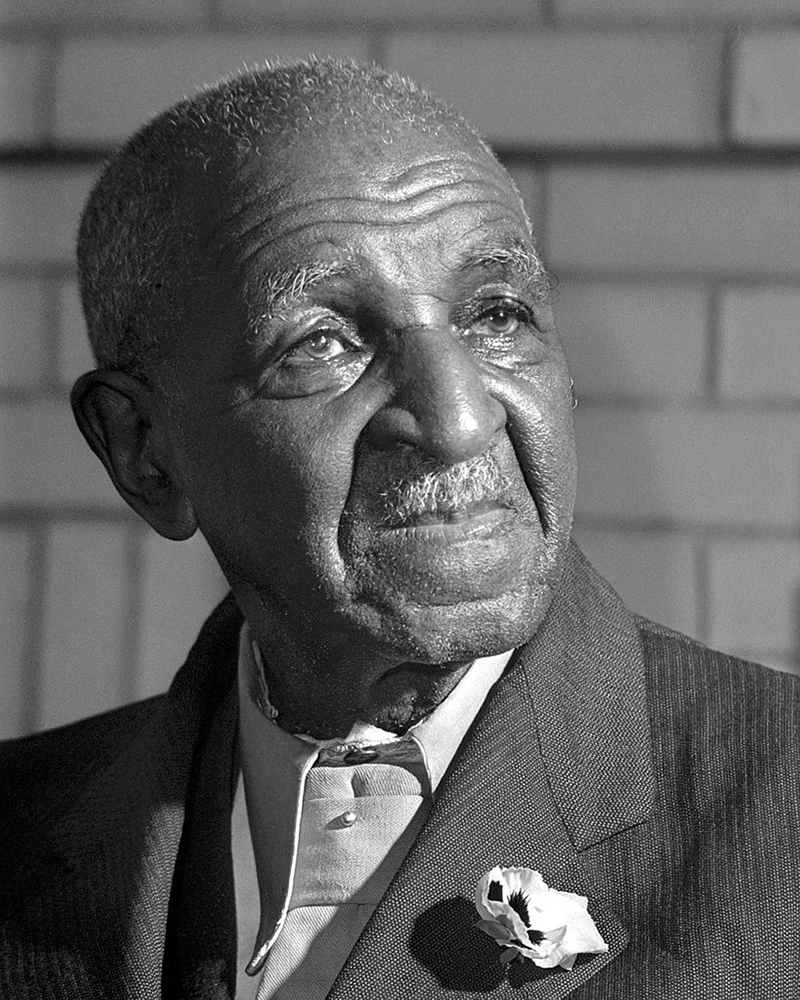

George Washington Carver

In some respects, in the United States this has long been true. Before the term “regenerative agriculture” was invented, the black agricultural scientist George Washington Carver was researching how to help poor black (and white) southern farmers whose soil had become severely depleted after years of growing cotton and tobacco. He famously advocated for crop rotation and the use of plants that could naturally restore nitrogen to the soil and help it recover. His work with peanuts came out of this endeavor. The legume, which didn’t originally appear to have a lot of monetary value except as a cover crop, could be eaten by sharecroppers and livestock. But Carver invented more than 300 uses for the peanut, enough for it to be considered a viable cash crop in its own right.

In some respects, in the United States this has long been true. Before the term “regenerative agriculture” was invented, the black agricultural scientist George Washington Carver was researching how to help poor black (and white) southern farmers whose soil had become severely depleted after years of growing cotton and tobacco. He famously advocated for crop rotation and the use of plants that could naturally restore nitrogen to the soil and help it recover. His work with peanuts came out of this endeavor. The legume, which didn’t originally appear to have a lot of monetary value except as a cover crop, could be eaten by sharecroppers and livestock. But Carver invented more than 300 uses for the peanut, enough for it to be considered a viable cash crop in its own right.

More specific to regenerative agriculture, however, was work that came out of his experiments with crop rotation, cover crops and cultivation practices on a 10-acre field at Tuskegee University. In one trial on a half-acre section of this field, Carver was able to increase the yield of sweet potatoes grown on the land from 40 bushels to 266 bushels in just a few years without the use of commercial fertilizers. He then demonstrated that land that had been depleted by growing cotton could also recover in a similar fashion with significantly increased yields of cotton when it was replanted a few years later.

But Carver’s work didn’t stop there.(opens in new window) He intended that “every operation” he performed on his university land could be duplicated by a "poor tenant farmer with one-horse equipment." He was also devoted to the idea of putting this information into the hands of those farmers by creating traveling agricultural schools that would go from town to town teaching them how to be self-sufficient by using fertilization and the best crops to grow in various soils. This project was eventually taken on by the USDA who added guarantees against losses if a farmer adopted the practices chosen for their particular piece of land.

Soul Fire Farm and Pie Ranch

Today, the work of George Washington Carver continues to inspire and support the work of the BIPOC community (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) fighting for food and climate justice in such ventures as Soul Fire Farm(opens in new window) in Grafton, NY and Pie Ranch(opens in new window) in Pescadero, CA.

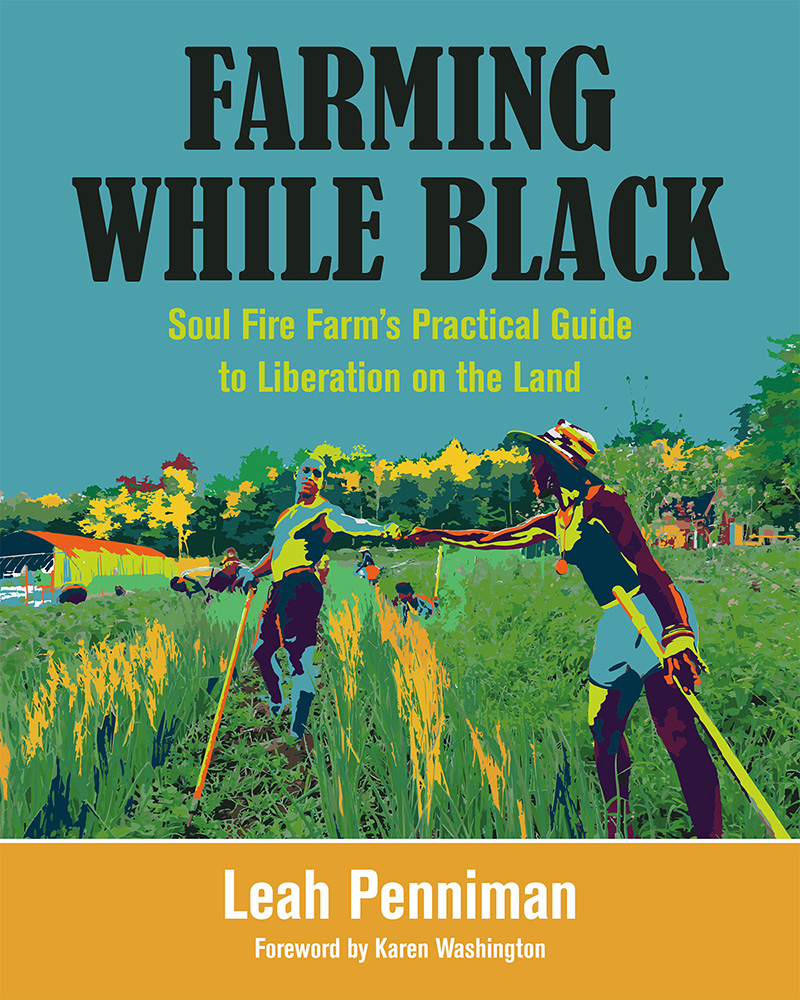

In 2005 Leah Penniman and her husband Jonah Vitale-Wolff started a community garden in order to feed their family and community in a part of Albany, NY that offered very few options for fresh produce. This led to the creation of Soul Fire Farm that, in addition to fresh produce, offers educational programs to train other people of color using the motto “to free ourselves we must feed ourselves.” In her book Farming While Black(opens in new window), Penniman celebrates the wisdom of Afro-indigenous people as leading the way for the sustainable agriculture practices used on the farm and in its classes.

In 2005 Leah Penniman and her husband Jonah Vitale-Wolff started a community garden in order to feed their family and community in a part of Albany, NY that offered very few options for fresh produce. This led to the creation of Soul Fire Farm that, in addition to fresh produce, offers educational programs to train other people of color using the motto “to free ourselves we must feed ourselves.” In her book Farming While Black(opens in new window), Penniman celebrates the wisdom of Afro-indigenous people as leading the way for the sustainable agriculture practices used on the farm and in its classes.

In particular, Soul Fire Farm is using regenerative practices to restore 80 acres of mountainside land to provide fruit, vegetables, meat, honey, and plant medicine primarily for people living in racism-fueled food deserts. These practices include no-till, cover crops, compost and manure, use of polyculture and native species, and silvopasture. Together they increase topsoil depth, sequester soil carbon, and increase biodiversity.

Similarly, Pie Ranch in Pescadero, CA, has recently acquired the 418 acre Cascade Ranch to be used as a regenerative farmer incubator program with a special emphasis on increasing equity, ownership, and wealth-building opportunities for women and people of color, who have been historically disenfranchised from land ownership and management. Led by Director of Operations and Farming Education, Leonard Diggs(opens in new window), the program will support multiple farming operations with subsidized access to land, equipment, and infrastructure as well as mentorship and guidance.

Like Penniman, Diggs points to indigenous cultures for lessons in how to interact with our natural resources in the face of climate change. He says, “The challenges now are how to integrate Indigenous peoples’ knowledge with what we currently know about the environment, and what we are doing in our regenerative farming and ranching practices.” Earlier in his career he was focused on the science of agriculture and biology, and later that morphed into exploring scientifically based organic and sustainable farming practices. Today, however, he says that “the ecological needs of the planet and the social, political and spiritual needs of the people are urging me to do more.” Most recently, because of the Covid-19 crisis, his work has pivoted to helping Pie Ranch provide produce to over 800 families on the coast and in the Bay Area through the Farm Fresh Food Relief Initiative done in partnership with the nonprofit Fresh Approach.(opens in new window)

Ameret Asefaw Berhe

Soil biogeochemist and political ecologist Ameret Asefaw Berhe has an opinion piece in the July 2020 Time Magazine segment on 2020 being a turning point for climate change. In her work as Professor of Soil Biogeochemistry and the Falasco Chair in Earth Sciences at UC, Merced, her research has been focused on how the soil helps regulate the earth's climate. In her opinion piece she wrote of the importance of being anti-racist in the fight against climate change. She said that “when people hear ‘Black Lives Matter,’ they don’t often think of climate change. But the location and nature of climate change’s worst effects on human society are geographically delineated by persistent legacies of racism, slavery and colonialism.”

Soil biogeochemist and political ecologist Ameret Asefaw Berhe has an opinion piece in the July 2020 Time Magazine segment on 2020 being a turning point for climate change. In her work as Professor of Soil Biogeochemistry and the Falasco Chair in Earth Sciences at UC, Merced, her research has been focused on how the soil helps regulate the earth's climate. In her opinion piece she wrote of the importance of being anti-racist in the fight against climate change. She said that “when people hear ‘Black Lives Matter,’ they don’t often think of climate change. But the location and nature of climate change’s worst effects on human society are geographically delineated by persistent legacies of racism, slavery and colonialism.”

Berhe advocates for the climate change community to address socioeconomic and political factors that are root causes of the climate crisis as well as serving to reduce access to resources and opportunities to people of color. She sees these as linked—especially since it is rare for her to find other dark-skinned colleagues in the scientific and educational sectors attempting to find solutions to the problem. And yet, marginalized communities are already suffering the effects of food and nutritional insecurity due to degraded and eroded soil, and climate change exacerbates the problem. While more prosperous white communities are already well-versed on the impact of rising temperatures affecting sea levels, thawing of the permafrost and the plight of the polar bears, they are far less likely to know how dire the situation is in terms of food security for everyone. From her perspective, amplifying the voices of those already suffering those consequences and those most vulnerable in the near future is essential for bringing the importance of soil more clearly into the public view. Those voices are also needed to contribute their own local and indigenous knowledge to mitigation and adaptation solutions. Since regenerating soil is essential for both food security and mitigating climate change, nothing could be more important.