To Save the Earth from Climate Change, We Need to Cover It Up!

by Sheryl Karas, RAI staff

The National Climate Assessment (NCA) report released by the federally mandated U.S. Global Change Research Program(opens in new window) last November included a terrifying prediction for farmers and our food supply. Increased drought, fire and floods, pest and disease outbreaks, increased soil erosion, depleted groundwater supplies, and degraded soil and water quality are just some of the “highlights.” The entire report(opens in new window) spells out disaster in every aspect of human life if not enough is done to lower greenhouse gas emissions and implement adaptation strategies. And the changes and problems have already begun.

Because food and water security are among the highest priorities, farmers are going to be on the front lines of combating climate change. And many if not most farm communities are already experiencing the early effects. Luckily, a movement is growing to give them the tools needed to fortify their farms and help us all weather the changes happening now. The secret is in the soil and the approach is called Regenerative Agriculture.

Healthy soil is full of organic matter and microorganisms that make farms more resilient. When roots from previous plantings and plant materials left after harvesting are allowed to remain in place, the fertility of the soil improves, it holds more water, and farms become less vulnerable to the impact of weather extremes. Not allowing the soil to be left bare and wide open to the elements is extremely important to this process. Unfortunately, this is not standard practice even though it is certainly not a new idea. Too many farmers in the U.S. watched as their bare soil blew away during the Dust Bowl. And farmers all over the world see their land and their livelihoods washed away in heavier than average storms. And yet making change, especially expensive change, for a traditionally risk adverse population is challenging, to say the least.

Of course, change will be forced with horrific consequences if nothing is done. So let’s focus on the least expensive and most effective approach to improving soil and increasing food and water security: the use of multi-species cover crops.

Success From Taking Cover

Back in 2009-2010, Dr. Roland Bunch(opens in new window) was involved in a 6-nation study for Africa for World Renew and realized to his growing horror that, due to poverty and diminishing farm size, traditional methods for letting the land recuperate between plantings by letting part of it lie fallow had been abandoned. As a result, the organic matter content and fertility of the soils was steadily dropping, crop yields diminishing, and 10 million people were fast heading towards famine.

Fertilizers do little good in soil so badly depleted so it wasn’t a useful solution for the cost. More and more of the land was becoming a wasteland, and food shortages and childhood stunting due to malnutrition were already starting to occur. So what could be done?

In this situation, “green manure/cover crops are the only feasible and sustainable route farmers can take,” says Bunch. Green manure is a ground-covering mulch and soil amendment created by leaving old roots and plant debris on the ground to dry and then incorporating it into the top level of soil. More than one cover crop that can provide a variety of nutrient qualities are usually chosen for this job. When those crops are edible they have the added benefits of being both a food source and additional source of income if the products are sold. That can be enormously valuable, especially in poverty-stricken regions.

According to Bunch, a farmer can produce over 100 tons of biomass (green weight) on two hectares of land. “This quantity of biomass is more than enough not only to maintain the fields’ fertility, but to gradually restore the soil, even on wastelands, to its naturally high fertility.”

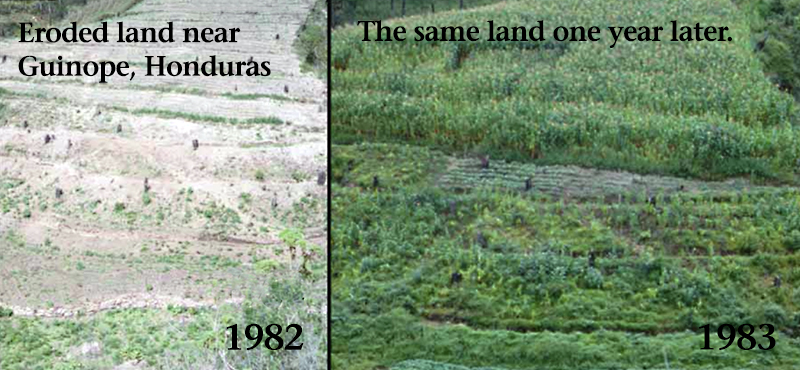

In fact, Bunch reports that surprising increases in soil fertility in a short period of time can be achieved using this approach. He says, “On at least 75% of the developing world's wastelands (basically those that have a pH of at least 4.5 and have not been polluted or salinized), we can have farmers growing crops within one to two years at the national average for most smallholder farmers in sub-Saharan African nations. Within four to six years, they can be producing two or three times the national averages.” He has documented such results (PDF) working with Oxfam/ America, Groundswell, the Canadian Foodgrains Bank, CARE and Catholic Relief Services while helping farmers in a dozen nations in Africa, Asia and Latin America.

More Benefits from Using Multiple Species

American farmers have become so used to monoculture (single crop) agriculture that sowing a variety of seeds at once might seem like a foreign, messy, and unnecessary concept. But Dr. Christine Jones, a preeminent soil microbiologist from Australia, believes it is essential because it supports the biology of the soil. And that supports the soil itself and the health of the plants.

According to Jones “over 95% of life on land resides in the soil” and they live in a deeply interconnected relationship with the plants above. Microorganisms feed off the sugars exuded by plant roots and, in return, with the help of networks of beneficial fungi, they increase the availability of minerals and other nutrients the plants require. Microbes also break down the organic plant matter produced by spent cover crops. That is, literally, what creates humus, the chocolate cake-like material that improves the soil’s structural integrity, aeration, infiltration and water-holding capacity. Well-structured soils are less prone to erosion and compaction so they hold up to extreme weather events better. They also function more effectively as bio-filters to remove pollutants from storm water run-off.

Jones emphasizes that a variety of cover crop plants make all the difference in supporting this biology. “Every plant exudes its own unique blend of sugars, enzymes, phenols, amino acids, nucleic acids, auxins, gibberellins and other biological compounds . . .The greater the diversity of plants, the greater the diversity of microbes and the more robust the soil ecosystem. Jones recommends that farmers “aim for a good mix of broadleaf plants and grass-type plants and include as many different functional groups as possible.”

Furthermore, in a drought or another extreme weather event farmers can lose everything they’ve planted at once. With multiple crops some types of plants may survive so you don’t lose everything and that will also keep the soil biology alive so it can regenerate. Some cover crop experimenters work with as many as 60-70 different species in their mix. But Jones says it doesn’t have to be that complicated. “Something as simple as including one or two companions with a main cash crop can make a world of difference. Indeed, it is becoming increasingly common to see peas with canola; clover or lentils with wheat; soybean, pigeon pea, fava beans, mungbeans or vetch with corn; flax with chickpeas; buckwheat and/or peas with potatoes … and so on.” The companions improve nutrient density while providing food for livestock or another edible product to sell.

But cover crop diversity has another amazing benefit to offer, and this may be one of the most important ones of all. It is also a strong predictor of the soil’s ability to store carbon . . . and that has implications for fighting climate change.

Cover Up for Climate Change!

Around the globe, it is most common for the land to be left bare for half the year. Only about 3% of all farmers in the United States, for example, currently make use of cover crops. That makes conventional farmland a source of carbon in the atmosphere as the carbon dioxide brought down by plants via photosynthesis is released back out.

But when land is covered, the soil can then act as a carbon sink, with the living roots and microbiology keeping the carbon sequestered in the soil. According to research(opens in new window) commissioned by SARE (Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education), “cover crops have the potential to sequester approximately 60 million metric tons of CO2-equivalent per year when planted across 20 million acres (8.1 million hectares), offsetting the emissions from 12.8 million passenger vehicles.”

Exciting possibilities! Let’s cover up and get it done.